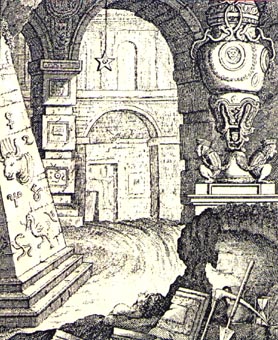

Frontispice of the Original Libretto |

Now that we had a chance to become familiar with the plot of this opera and perhaps also to take a look at the German libretto, we might be better prepared for an excursion into comments and music criticism. Let's begin it with a look at its further premieres outside of Vienna:

We have taken our information from the so-called Köchel Catalogue (of Mozart works):

Vienna was followed by Prague, October 25, 1792, Frankfort, April 16, 1793, Munich, July 11, 1793, Berlin, November 15, 1793, and Hamburg, May 12, 1794. The first staging in the Italian language followed on April 2, 1794, in Dresden (the translator was Giovanni de Gamerra, who earlier wrote the text to >Lucio Silla<). The first staging in London (in Italian) followed on June 6, 1811, at King's Theare, in German on May 27, 1833, at Covent Garden, and in English on March 10, 1911, at Drury Lane, followed by stagings at Old Vic. -- The first stagings in America occurred on March 7, 1832, in Philadelphia, and on April 17, 1833, in New York (in English) at the Park Theatre; -- In Paris: at the Theatre des Arts as Pasticio (with pieces from >Don Giovanni< and >Tito<) under the title >Les Mysteres d'Isis<, adapted by Morel de Chedeville und Lachnith, on August 28, 1801. On February 23, 1865, this was followed by an arrangement by Barbier, Nuitter und Beaumont at the Theatre lyrique, and on May 31, 1909, by a new adaptation by Bisson and Ferrier at the Opera-Comique. A first faithful version, through Jules Kienlin und J.-G. Prod'homme was staged in Brussels on December 21, 191, and subsequently, on December 22, 1992, at the Paris Opera. -- Further first stagings occurred on April 15, 1816, in Milan, on February 13, 1817, in Amsterdam (in Dutch), and on May 24, 1818, in Petersburg (Köchel Catalogue: 792).

We already know what Goethe's mother had to report of one of the Frankfort stagings of this work. What did her son think of it? We already know that Mozart's Entführung aus dem Serail 'spoiled everything' for him with respect to his own attempts at writing singspiele for the Weimar stage in the early 1780's. In the 1820's, Eckermann collected his conversations with Goethe. One of them also discussed Mozart's opera:

"Montag, den 13. April 1823

Abends mit Goethe allein. Wir sprachen über Literatur, Lord Byron, dessen >Sardanapal< und >Werner<. Sodann kamen wir auf den >Faust<, über den Goethe oft und gerne redet. Er möchte, daß man ihn ins Französische übersetzte, und zwar im Charakter der Zeit des Marot. Er betrachtet ihn als die Quelle, aus der Byron die Stimmung zu seinem >Manfred< geschöpft. Goethe findet, daß Byron in seinen beiden letzten Tragödien entschiedene Fortschritte gemacht, indem er darin weniger düster und misanthropisch erschein. Wir sprachen sodann über den Text der "Zauberflöte", wovon Goethe die Fortsetzung gemacht, aber noch keinen Komponisten gefunden hat, um den Gegenstand gehörig zu behandeln. Er gibt zu, daß der bekannte erste Teil voller Unwahrscheinlichkeiten und Späße sei, die nicht jeder ruechtzulegen und zu würdigen wisse; aber man müsse doch auf alle Fälle dem Autor zugestehen, daß er im hohen Grade die Kunst verstanden habe, durch Kontraste zu wirken und große theatralische Effekte herbeizuführen".

(Eckermann: 457; "Monday, the 13th of April, 1823: Alone with Goethe in the evening. We talked about literature. Lord Byron, his >Sardanapal< and >Werner<. Then we discussed >Faust<, about which Goethe likes to talk often. He wants it translated into French, and that in the character of the era of Marot. He sees it as the source, from which Byron took the mood of his >Manfred<. Goethe thinks that, in his last two tragedies, Byron has made considerable progress in that he appears less gloomy and melancholy. Then we discussed the text of the "Magic Flute", of which Goethe has written a sequel, but not found a composer, yet, in order to treat the subject appropriately. He admits that the known first part is full of improbabilities and jests that not everybody would be able to decipher and enjoy in the right manner; however, he had to admit, that the author has understood the art of working with contrasts to a high degree and to achieve great theatrical effects with it").

An operatic genius such as Richard Wagner was, of course, also hard pressed to ignore the influence of this opera:

"Welch ungezwungene und zugleich edle Popularität in jeder Melodie, von der einfachsten zur gewaltigsten!" rief er aus. "in der Tat, das Genie tat hier fast einen zu großen Riesenschritt, denn, indem er die deutsche Oper erschuf, stellte er zugleich das vollendetste Meisterwerk derselben hin, das unmöglich übertroffen, ja dessen Glanz nicht einmal mehr erweitert und fortgesetzt werden konnte".

(Kolb: 290; "What an un-forced and, at the same time, noble popularity in every melody, from the simplest to the greatest!", he is reported as having exclaimed, "indeed, the (Mozart's) genius almost took a too gigantic step here, since, in creating German opera with it, he also created the most perfect masterwork with it, that can hardly be surpassed, nay, the glamour of which could not be extended or continued").

In the first part of the 20th century, Alfred Einstein rendered one of the most interesting comments of this era to the Magic Flute:

"One's judgment of the libretto of Die Zauberflöte is a criterion of one's dramatic or rather dramatico-musical, understanding. Many critics find it so good that they deny its authorship to poor Schikaneder and ascribe it to the actor Carl Ludwig Gieseke, whose real name was Johann Georg Metzler, who had added the study of mineralogy to that of law, and in 1783 had become a comedian and joined Schikaneder's company. In 1801 he bade farewell to the stage, became Royal Director of Mines in Denmark and, in 1814, Professor of Mineralogy and Chemistry at the University of Dublin, where he died, When he visited Vienna again about 1818 or 1819 he is supposed to have claimed the authorship of the entire text of Die Zauberflöte. But if he wrote any of it at all, it was at most Tamino's discourse with the Speaker, the diction of which is somewhat above Schikaneder's powers.

For the weakness of the libretto--a small weakness, easily overcome--lies only in the diction. It contains a great number of unskilful, childish, vulgar turns of speech. But the critics who therefore decided that the whole libretto is childish and preposterous deceive themselves. At any rate Goethe did not so consider it when he wrote a 'Zauberflöte Part II', unfortunately unfinished but full of fairy-tale radiance, poetic fantasy, and profound thought. In the dramaturgic sense Schikaneder's work is masterly. The dialogue could be shortened and improved, but not a stone in the structure of these two acts and of the work as whole could be removed or replaced, quite apart from the fact that any change would demolish Mozart's carefully thought out and organic succession of keys.

Nor can I find the slightest evid3ence for the claim that Schikaneder, after finishing the first half of his libretto, changed the course and characters of his opera because of the production of a competing opera at the Leopoldstädter theater.

. . .

All this is enacted in a fairy-tale atmosphere: three genii float down to make reports, to impart instruction, and to ward off catastrophes; two mean in armor stand before the portal through which Pamina and Tamino pass to undergo the final test, that of fire and water; Papagena, the mate intended for Papageno, appears to him at first in the guise of a wrinkled hag; Tamino's flute allures and tames all the beasts of the wilderness; Papageno's glockenspiel drives Monostatos and his black constabulary into a frenzied dance. This all seems merely a fantastic entertainment, intended to amuse suburban audiences by means of machines and decorations, a bright and variegated mixture of marvelous events and coarse jests. It is such an entertainment, to a certain extent; but it is much more, or rather it is something quite different thanks to Mozart. Die Zauberflöte is one of those pieces that can enchant a child at the same time that it moves the most worldly of men to tears, and transports the wisest. Each individual and each generation finds something different in it; only to the merely 'cultured' or the pure barbarian does it have nothing to say. Its sensational success with its first audiences in Vienna arose from political reasons, based on the subject-matter. Mozart and Schikaneder were Freemasons: Mozart an enthusiastic one, and Schikaneder surely a crafty and active one. The latter used the symbols of Freemasonry quite openly in the libretto. The first edition of the libretto contained something rare in such books--two copperplate engravings, one showing Schikaneder-Papageno in his costume of feather, but the other showing the portal to the 'inner rooms,' the great pyramid with hieroglyphics, and a series of emblems: five-pointed star, square and trowel, hour-glass and overthrown spars and plinths. Everyone understood this. After a period of tolerance for the 'brothers' under Joseph II. a reaction had set in with Leopold II, and there had begun again secret persecutions and repressions. The Queen of the Night was Maria Theresa, Leopold's mother; and I am convinced that the black Traitor Monostatos also was intended to represent a particular personage. Under to cloak of symbolism Die Zauberflöte was a work of rebellion, consolation, and hope. Sarastro and his priests represent hope in the victory of light, of humanity, of the brotherhood of man. Mozart took care, by means of rhythm, melody, and orchestral color, to make the significance of the opera, an open secret, still clearer. He began and ended the work in E-flat major, the Masonic key. The slow introduction of the Overture begins with the three chords, symbolizing the candidate knocking three times on three different doors. A thrice-played chord follows Sarasto's opening of the ceremonies in the temple. Woodwinds--tye typical instruments of the Viennese lodges--play a prominent part; the timbre of the trombones, heretofore used by Mozart-- in Idomeneo, in Don Giovanni--only for dramatic intensification, now takes on symbolic force.

These Masonic elements had little meaning for the 'uninitiated' and have had even less for later generations. What remains is the eternal charm of the naive story, the pleasure in Schikaneder's skill--what a master-stoke, to bring the lovers together in full sight of everyone in the finale of Act I!--and the wondering awe at Mozart's music. The work is at once childlike and godlike, filled at the same time with the utmost simplicity and the greatest mastery. The most astonishing thing about it is its unity. The Singspiel, the 'German Opera', had been from its very beginning a mixture of the most heterogeneous ingredients: French chanson or romance, Italian aria or cavatina, buffo ensembles, and--the only thing German in it, aside from the language--simple songs. This is true of Die Zauberflöte also. The Queen of the Night's great scena (No. 4, O zittre nicht, mein lieber Sohn) and aria (No. 14, Der Hölle Rache kocht in meinem Herzen), written for Mozart's sister-in-law Josefa Hofer, are pieces in purest opera-style, stirring, or full of passionate force, with elaborate coloratura passages; but the coloratura also serves to characterize the blind passion of the direful Queen. At the other extreme is Papageno's little entrance song (No. 2, Der Vogelfänger bin ich ja), which would have been a street song if Mozart had not ennobled it with his wit and the genius of his instrumentation; or Papageno's magic song with the glockenspiel (No. 20, Ein Mädchen oder Weibchen); or his burlesque suicide scene and the droll ensuing duet (pa ... pa ... pa ...) with Papagena. Between the two extremes are the pieces sung by Tamino, Pamina, and Sarastro--Tamino's 'Portrait Aria' (No.3); Pamina's moving plaint in G minor, when Tamino can answer her questions only with sighs (No. 17, Ach, ich fühl's, es ist verschwundenI); Sarastro's famous exhortation (No. 15, In diesen heil'gen Hallen); and the little duet between Pamina and Papageno (No. 7, Bei Männern, welche Liebe fühlen), which is a song in two strophes. Are they Italian; are the German? One can say only that they are Mozartean, in their combination of purest expression with purest melody; they are cantabile but not Italian; they are simple, but much too rich in expression, far from simple enough, much too sensitive in every turn of the voice part, every shading of the accompaniment, to fit into the category of the German Lied. Similarly with the relation of the ensembles and the two great finales to opera buffa. Where would a place have been found in opera buffa (opera seria does not enter into consideration at all here) for the trios of the three boys, which, in their transparent shimmer, seem drawn from a new domain of music, the domain of Ariel; or for the scenes of the three ladies, which are so humanly amusing and at the same time so imperious. But above all there was no place in opera buffa for the chorus, with which Mozart achieves the loveliest and most imposing effects in his work.

The most imposing effects! The mixture and fusion of the most heterogeneous elements in Die Zauberflöte are truly incredible; Papageno, with a padlock on his prattling lips, may make desperate signs to the three ladies; or Monstatos, to a pianissimo accompaniment of the orchestra, may perform his grotesque phallic dance before the sleeping Pamina--but no sooner does Mozart strike to mood of intense seriousness than we are in the true, innermost magic circle of the work. The March of the Priests and Sarastro's invocation (No. 10, O Isis und Osiris) introduced a new sound to opera, far removed from churchliness: it might be called a kind of secular awe. Two pieces particularly contribute to this new sound. In the first act it is the beginning of the finale, with the trombones, muted trumpets, sustained notes in the woodwinds, and the luminous voices of the trio of boys--the solemn introduction to Tamin's dialogue with the old priest. We are at one of the central points of the work: when Tamino, after this grave dialogue, asks himself:

O ew'ge Nacht! Wann wirst Du schwinden?

Wann wird das Licht mein Auge finden?

[O endless night! hast thou no breaking?

When dawns the day mine eyes are seeking?]and the invisible choir answers him consolingly, we sense the dawn of a better world. In the second act it is the final test of the lovers, the 'test of fire and water,' for which Mozart called into play every musical means at his disposal and for which he ordained extreme simplicity, extreme mastery; the scene of the men in armor, which he constructed in the form of a chorale prelude, building upon a solemn fugato around the chorale Ach Gott vom Himmel sieh' darein; the blissful and serious muted slow march of the wind instruments of Tamino's flute; the C major jubilation that greets the sucessful conclusion of the test.

There are two ways of approaching Die Zauberflöte. Mozart had occasion to observe both of them in reactions of contemporaries. . . . [Here, we refer the reader back to the creation history page and Mozart's letters to Constanze of October, 1791, in one of which he reports of the 'notorious Bavarian' who laughed to everything in the opera, even the serious passages, and to his report of Salieri's delight with the opera] . . . It was his bequest to mankind, his appeal to the ideals of humanity. His last work is not Tito or the Requiem; it is Die Zauberflöte. Into the Overture, which is anything but a Singspiel overture, he compressed the struggle and victory of mankind, using the symbolic means of polyphony; working out, laborious working out in the development section; struggle and triumph" (Einstein: 463 - 468).

In the 1970's, the German writer Wolfgang Hildesheimer arrived at quite different views with respect to the Magic Flute:

"No opera of Mozart's has stimulated biographers' wishful thinking in such rich measure as Die Zauberflöte. It is considered his swan song, a concluding apotheosis, a return to divine simplicity. Actually, nowhere are Mozart's extramusical ambitions as clear as in Die Zauberflöte. Sentimental Mozart interpreters cannot reconcile themselves to the fact that although he sets markers beside each stage of his musical style (or styles), he does not scatter them throughout his life so that we may gauge his world view. Thus, critics in search of a reconciled rounding off to his life, a harmonious dying away, have succeeded in forcing upon Die Zauberflöte the marks of transfigured wisdom, the qualities of a late work, as in for example, the duality of Tamino-Papageno. According to Abert, "The text corresponds so perfectly to his view on opera that we have no qualms in assuming that the composer had a great share in it." Here again is that desire for a correspondence between life and work, the same one that led to the idea that Shakespeare is embodied in Prospero, the protagonist of the "late work" The Tempest (although he was only forty-seven years old when he wrote it). For us the wok on Die Zauberflöte is a last, energetic attempt to achieve solvency, even if it meant a concession to "popular" taste. There is ample evidence that Mozart had long ago stopped caring about "pleasing," as such. But how else can we explain his birdcatcher, except to conclude that this carefree, merry fellow was meant to be profitable for his creator?

Because, to the sorrow of many, nothing authentic is known about the collaboration of librettist and composer, there are countless insidious legends about the creation of Die Zauberflöte. . . .

Biographers claim that this work, in particular, was an inner necessity for him that here, more than in any other opera, Mozart was able to realize his humanitarian ideals. But, in fact, there is absolutely no verifiable basis for this view, nor for the idea that here at last he could seize the welcome opportunity of writing a German opera. True, in some early letters to his father he had championed things "Teutsche"; this apparent attachment culminates in a letter of 1785 to the librettist Anton Klein in Mannheim, in which he complained about the "directeurs des theaters":

Were there but one good patriot in charge--things would take a different turn. But then, perhaps, the German national theater which is sprouting so vigorously would actually begin to flower; and of course that would be an everlasting blot on Germany, if we Germans were seriously to begin to think as Germans, to act as Germans, to speak German and, Heaven help us, to sing in German!

Naturally, this passage was a happy find for every nationalistic and patriotic cultural history: "Mozart's German way" (Alfred Orel) seemed assured and proven once and for all. In reality, of course, this is another passage that should also be in quotation marks, a momentary fit of patriotic chest thumping. His real purpose was to use pretty speeches to shake off Herr Klein, who had sent him a libretto entitled Kaiser Rudolf von Habsburg. We must admit that the thought of Mozart composing an opera bi this name is not without a certain absurd charm.

How little sporadic wishes to compose to German texts reflect his patriotism is evident from the fact that, as early as 1783, he imagined a suitable text for a "German" opera to be a translation of Servitore die due padroni by Goldoni (we, too, think it would be suitable). No one has ever been able to accept the idea that all the intentions or desires he expresses in his letters are literally of the moment, his behavioral response to a particular fleeting stimulus, and often also an unconscious desire to adapt to the situation. He wanted to please the addressee.

Those passages, however, in which he tells his father of his intentions as a composer, and exhorts him urgently to support him in their realization, are always truthful and significant. On February 4, 1778, he wrote to him from Paris: "Do not forget how much I desire to write operas. I envy anyone who is composing one. I could really weep for vexation when I hear or see an aria. But Italian, not German; serious, not buffa." A few days before, on the other hand, on January 11, 1778, he had written to his father in a postscript: "If the Emperor will give me a thousand gulden, I will write a German opera for him." One could not say that a national ideal was paramount here. Mozart cannot be pinned down by his written wishes or opinions; his artistic will was expressed only after the fact, in each respective work. In the last analysis, he was interested exclusively in the works themselves, and not in the realization of a "mission" (Hildesheimer: 310-313).

And with respect to the Masonic content of the opera:

"Since we know nothing about Mozart's share in producing the libretto, we cannot judge if the Freemasonry implicitly advocated in it reflected his active intention or even his particular wish. The image of Mozart the Freemason has often been idealized; he certainly was caught up in an ew wave of interest when in December 1784 he joined the lodge Zur Wohlthätigkeit (Benevolence), to which Karl Ludwig Giesecke, the other poet of Die Zauberflöte, also later belonged (Schikaneder did not belong to any lodge). The lodge Zur Wohlthätigkeit was less important than Zur gekrönten Hoffnung (Crowned Hope); it was considered a "gorging and boozing lodge," this it is not certain who coined this phrase.

The Masonic ideal of human brotherhood, though undoubtedly praiseworthy for the time (although it actually had more to do with male brotherhood), indeed revolutionary in its moral goals and general ethical concepts, was expressed only in vague proclamations. More a matter of words than deeds, much sung about--and always badly--Freemasonry never led to any real theory, nor would Mozart have been interested if there had been one. The "meaning of life", man's task on earth--these were not things he wondered about consciously. On the other hand, he needed company, and he found it in the lodge. When his duty as a composing lodge brother ordained that he write music for celebrations or funerals, he wrote it. He used his own sacred style, the solemn stance, which usually miscarried when he had to keep to the texts. Heavy, well-meaning but ineffectual, they were written by gentlemen such as Ziegenhagen, Ratschky, or Petran (honorable men, but amateur poets) [or by Herr Giesecke]. The essence of the art work lay in the text; it could not be genaralized musically. The massage had to be kept intact; at most, Mozart could use pathos to accentuate it. These compositions have the forced quality of required exercises. It was much harder for Mozart than for Beethoven to set the word "mankind" to music.

The non-verbal Masonic music is a different matter. Apart from the marches of Die Zauberflöte, we have only the splendid and unique Masonic Funeral Music, K 477/479a, of November 10, 1785, commissioned after the death of two members of Zur gekrönten Hoffnung, the Duke of Mecklenburg and Count Esterhazy. This piece, like the Ave verum Corpus, is one of the most wonderful occasional works ordered and delivered punctually and in perfect condition by the great man, himself as little involved as a painter who paints a burial scene. Two illustrious lodge brothers have died; Mozart has to paint the picture and he paints it. He brings it forth at a majestic distance, a painting of grief, grand and controlled, perfect from the beginning, with its huge sighing motifs in C minor and the cantus firmus in E-flat major, to the final cadence in C major, like a signature at which he withdraws with a bow, leaving his work behind. We can no more see it as a "personal expression of Mozartean feelings about death" (whatever that may be) than as his "surrender to death."

But Die Zauberflöte is not a Masonic cantata, however much the main plot may be infused with the strange, secretive Masonic ethos. It is a German Singspiel, originally an entertainment for the theaters of the outer city, a "comedy with machines" (today we would say a "musical"), with harsh, gaudy stage illusions laid on lavishly by Schikander. Yet, in the serious sections, Masonic symbolism and morality form the essential theme, the theoretical components underlying the ostensible action, which is a cipher destined for a flooded of interpretations." (Hildesheimer: 314 - 316).

And on the quality of the libretto:

"Goethe's remark to Eckermann on April 13, 283, that Die Zauberflöte is full of "improbabilities and jokes, which not everyone is capable of understanding and appreciating," does, it is true, have something of the nature of a defense against expected attacks. But it was none other than Goethe who laid the cornerstone for the positive evaluation of the text, with an assertion that Schikaneder admirers wear like badge; it legitimizes them and vindicates them. Goethe declared, "It takes more education to appreciate the worth of this libretto than to deny it," There we have it. So defenders of the libretto usually begin, "No less a man than Goethe . . . " etc. Since Goethe, there has been a pious tradition of explaining away the opera's meaningless action by invoking its "hither meaning" (Goethe). Those with a "loftier consciousness" feel like "initiates" in the sense of the text; like Tamino and Pamina, they have passed the tests, while we uninitiated skeptics, unable to get beyond the nonsense, have to stick to the low level of Papageno, who would not exchange the tangible material world for a vague promise of an ideal world, sight unseen. The sacraments are with held from the uneducable, and so we stand and ask, for example, 'in whose service the Three Boys are bound, or why the Queen of the Night did not take up the magic flute herself to prevent her daughter's abduction. Did she have trouble playing the instrument, when even the foreign prince Tamino, to whom she presents it, can master it at once? And these are merely questions selected at random" (Hildesheimer: 316 - 317).

With respect to Mozart's dealing with the lack of logic in the plot:

"Of course, not even a Mozart could come up with a device to correct a lack of logic, especially the fatal want of continuity in the action. He could not give it the consistent musical line of the Da Ponte operas, the breathlessly surging power of Don Giovanni or the ironic sovereignty of Cosi fan tutte--there were libretti in which he almost literally guided the action. In addition, the secco recitatives and, specially, the accompagnati of Italian opera were able to create a harmonic and dynamic logic in the sequence of arias (and did so in Mozart's work in a truly unique way). The spoken dialogue of the Singspiel works against logic; at each such break our bubble is suddenly burst, not least because opera singers can seldom handle these speeches. It is hard enough to sing Tamino, and even harder to act the role, to master, for example, the mime with which, like Orpheus, he has to gesture rejection to his sweetheart, Pamina, much against his will. And what member of the audience does not shudder at the exaggerated diction, the Christmas-pageant solemnity, the strained hollow laughter of the men or the tinkly laughter and teasing ingenue mannerisms of the women? (A rhetorical question. The answer is that hardly anyone does, unfortunately.)

Because of the arbitrariness with which the characters represent now this, now that abstract principle, and their need to articulate these inconsistent views, the composer was unable to control their conception and development. He had to take each number as it came, determine its relative value and momentary significance, and adapt his music both to the character's particular change in situation and to his change in attitude. Thus, the representative of the negative principle, the Queen of the Night, is introduced in G minor as a tragically bereft mother; after rehearsing her grief (No. 4), she promises her daughter to the hero, Tamino, but in the very same aria, in the key of B-flat, she is transformed into a resolute demon; she is no longer the same woman. In the second act she becomes a larger-than-life villain in D minor ("Der Hölle Rache kocht in meinem Herzen," No. 14), the enemy of the son-in-law she had selected, and confederate of the evil Moor, Monostatos, to whom she promises her daughter in marriage, the same daughter for whose sake she has allegedly been grieving. There is no thematic or personal resemblance between the birdcatcher Papageno, who calls "heisa-hopsasa" in G major (No. 2), and the meditative E-flat major Papageno of the duet with Pamina (No. 7). We concluded that in between he has begun to think, and this does not suit him. We do not quite understand how love "rules Nature's own way." Even Monostatos, the Moor, undergoes his transformations: "as a human" he is different from his role as the lowest of the low. Probably Johann Nouseul, whose task it was to portray this cowardly, single-minded spoilsport, Osmin's dull brother, wanted an aria too. And he got one: "Alles fühlt der Liebe Freuden" (No. 13), a musically undemanding allegro in C major, above which Mozart wrote in the score: "To be played and sung a softly as if the music were a great way off." What might that mean? Perhaps it is the great distance from the Moor's native land. We do, in fact, seem to hear the echoes of janissaries in the distance: the piccolo, in unison with the flute, and the first violins (an octave below) produce a strange sound; at any moment a shift to A minor seems imminent, but it doesn't happen. No panorama opens up; rather everything remains one-dimensional in this lascivious yet flat tone behind which the Moor is certainly concealing his true intentions vis-a-vis the white maiden Pamina. We don't believe he just wants to kiss her; after all, he orders the moon to hide its face. This sad Moor is excluded from all good will; even the generous Masonic ethos won't go that far. For a moment he is granted mercy, but the next minute it is withdrawn" (Hildesheimer: 318-319).

With respect to the misogyny of the opera:

"The preoccupation with "females" (in Cosi fan tutte still an acceptable slight, because both sexes receive the same treatment) gets on our nerves in Die Zauberflöte. Nowadays this convention seems comic only in moderation; and in this case, too, no one has benefited from experience in life. We cannot assume that women's promiscuity at the tame was any worse than men's, although, unlike men's, it was not sanctioned. And in Die Zauberflöte women are always presented, annoyingly, as "little pigeons". Mozart certainly never addressed his Constanze by that name, nor did Schikaneder use it for his various ladies, and we do not know if Giesecke was in the habit of addressing ladies at all. Probably not, since he is most likely the one responsible for the misogyny. As we have mentioned, neither Mozart nor Schikaneder had misogynist inclinations, and their insistent advocacy of the Masonic ideal of male supremacy is therefore surprising. Under these circumstances, it is amazing that Pamina is allowed to incorporate the positive principle, that she, too, is deemed worthy of initiation, and is, in fact, initiated. Only Papagena, like her dear little husband, has to remain on a lower plane, but she feels quite at home there. Even noble Tamino, a kind of Parsival figure, is infected wit this attitude: "Silly nonsense, spread by women," he answers his companion when Papageno requests an explanation. The Queen of the Night is "a woman, has a woman's mind," and a few hours (as far as one can speak of a time sequence) after the Three Ladies save his life, he calls them "common rabble." He quickly learned from Sarastro's priests that man is superior to woman; he has it hammered into him continually, as, for example, in the two priests' duet "Bewahret euch vor Weibertücken" ("Beware of women's wiles") (No. 11). In a light, apparently gay C major the two moarlize to him, treating the case of a man who did not follow their advice and met a horrible end: "Tod und Verzweiflung war sein Lohn" ("Death and despair were his reward". The fact that this would be a post mortem despair is not the only inconsistency in their teaching. But Mozart could not do anything with the inconsistency; he was a keen, a brilliant musical thinker; a verbal message stimulated him immediately to its interpretive possibilities. . . . The bad end of the "wise man" who let himself "be ensnared" is portrayed neither in the sotto voce of the two voices nor in the strangely alienated staccato of the trombones. On the contrary, just where the text would seem to prescribe solemnity, the music becomes positively merry; the four-measure postlude turns into a jolly march. As so often in Die Zauberflöte, Mozart was here composing against the text. Or does this alienation reflect an intention we can no longer recognize? . . . Nevertheless, the message of the two priests seems to have stayed with Mozart in a strange way. At the end of a letter of June 11, 1791, to Constanze in Baden, he writes: "Adieu--my love! I am lunching today with Puchberg. I kiss you a thousand times and say with you in thought: 'Death and despair were his reward!' Obviously this line had pursued him into his private life, but whatever it might mean here will always remain obscure: could he be making light of a presentiment?" (Hildesheimer: 320-321).

With respect to the importance of the Magic Flute:

"The importance of Die Zauberflöte within Mozart's oeuvre has always been overestimated. The sacred, monumental quality--the waving of palm branches, the long robes, the pious processisions--is strange and un-Mozartean; it seems as if they were forced upon him. The prosodic recitatives of the priests and near-priests, these strophis arias ("song-like structures" [Paul Nettl]--all this makes the opera into a work sui generis and inimitable, to be sure, but not something complete and successful within itself. To be sure, Mozart's music is for long stretches at its highest level. But it was conceived as an unpretentious entertainment, and is not equal to the pretentious claims made for it later.

There are erors in criticism of the opera which stem, not from the experience of the work itself, but from extraneous theoretical factors: the importance of the creator, the choice of a subject in accordance with an ethos (an essential element of Fidelio), the atmosphere and conditions of the composition. These factors tend to replace one's judgment about the thing itself, or at least they prejudice it, and their influence grows ever greater as each new judge adopts some of the existing opinions. The thing itself has to be good, for geniuses, even in the service of lesser minds, have to be great, right up to the dying day, which, in the case of the composer of Die Zauberflöte, was not far off. Without doubt, this apotheosizing vision plays a role in judging the opera" (Hildesheimer: 327-328).

In the late 1980's, H.C. Robbins Landon, in the chapter on the Magic Flute of his book, "Mozart's Last Year", comments again quite differently:

"Mozart obviously found the amazing diversity of the subject immensely attractive. In the final score, this ranges from the Haydnesque folk-tunes of the music for the 'simple' beings, Papageno and Papagena, to the mystical and ritualistic music for Sarastro and his court, and from the mad colorature of the Queen of the Night (and the raging Sturm und Drang of the second aria, in D minor, Der Rölle Rache (The revenge of Hell), which recalls so many other Mozartian works in that key), to the inclusion of an antique-sounding north German Lutheran chorale tune, sung by the two men in armour. It was this same diversity that so impressed Beethoven (who in any case disapproved of Da Ponte's texts for the Italian operas as being too frivolous) and which impresses us, too" (page 127).

Iin the same chapter, with respect to Mozart's and Schikaneder's reasons for giving this opera a 'Mason' character:

"Now there must have been very urgent reasons for Mozart and Schikaneder to break this rule of silence. (The same formula, more or less, existed in the German-language St John Ritual). And while on this subject, it was suggested long ago (and this suggestion has been put forward even more strongly by three German doctors in book entitled Mozarts Tod, published in 1971, where they actually use the words 'ritual murder') that the Masons killed Mozart. There are, very simply, two facts which render this theory--which is considered very attractive in some quarters even today--not only unlikely but impossible. The first is that no one killed Schikaneder, who was just as responsible for 'betraying Masonic secrets' as Mozart. (Schikaneder had entered the Craft in Regensburg but had never joined a St John Lodge in Vienna.) For Schikaneder went on to live to what was then a ripe old age of 61 and died in 1812 (mad, it is true, but the Masons cannot have been responsible for that since they officially ceased to exist in 1795 and Schikaneder's death occurred seventeen years later). And the second reason is equally, if not more, convincing: Mozart's own Lodge Zur gekrönten Hoffnung held a Lodge of Sorrows for their composer, printed the main speech, and also printed the Masonic cantata (K. 623), Mozart had composed just before he died.

No, there must have been another reason why Mozart and Schikaneder were permitted to choose an opera subject glorifying Masonry. It is a point which many scholars have either neglected or misunderstood, but one which can be solved by examining the Masonic files that were kept by Austrian police at this period. The fact of the matter is that Freemasonry in Austria was in acute danger of extinction--just how acute may be judged by the fact that the Masons voluntarily closed their Lodges in 1794, while in 1795 a young and new Emperor forbade all secret societies, including of course the Masons. The reason for this sudden danger in which the Masons found themselves was their supposed involvement with the French Revolution and Jacobinism, and with a similar movement in Austria which the secret police--rightly, as it turned out--suspected of existing.

This meddling in revolutionary ideas went further back than 1789, the beginning of the leading Americans who broke away from England and declared their independence had been masons, including Franklin, Washington, Jefferson (who formulated the extremely Masonic-sounding Declaration of Independence), and so on. This fact was known not only to members of the Craft in Europe but also to the sovereigns and their police. In 1789, many of the leading members of those groups in favour of a republican government in France had been Masons. But in the event, the Craft collapsed during the Terror: the Grand Orient in Paris closed its doors in 1791, and by 1794 Freemasonry in France had practically ceased to exist. Many of the French Masons had wanted a republican kind of government, but in 1789 they certainly had no ideas of regicide in the back of their minds. On the contrary, many leading Masons were aristocrats and/or members of the royal government. Hence when one courageous Mason managed to reconstitute the Grand Orient in 1795, he found most of its members dead. A nineteenth-century historian of Freemasonry argues: 'If we consider that the members of Grand Orient had in great part consisted of personages attached in one way or another to the court of Louis XVI, we shall not be surprised to find that even on June 24, 1797, the number which assembled was only forty . . . The first new constitution was issued to a Geneva Lodge, June 17, 1796, and the report of June 24 only includes eighteen Lodges, of which three met at Paris.'

In Vienna, when The Magic Flute was being staged, Leopold II was watching with increasing apprehension the events in France, and this same apprehension was growing to a fear, almost paranoid in its intensity, in the minds of the secret police and other members of the Austrian government. At the outset of his reign, Leopold II was by no means inimical to the Craft, and Count Zinzendorf actually heard that Leopold had been a member of the Sovereign Prince Rose-Croix in Italy--a report which, of course, cannot be confirmed or denied. In any case, organizations like the Illuminati, the Strict Observance, the Asiatic Brethren, the St John Masons and even (if it is true he belonged to it) his former Rose-Croix all now seemed much more dangerous to the Emperor and his advisers" (Pages 132 - 133),

and further:

"In the face of such suspicion and hostility, how was Masonry to be protected? How were its greatness and universality to be presented to the general public? The two Masons, Mozart and Schikaneder, decided to write the first Masonic opera--The Magic Flute. Wisely, they treated the whole subject in two ways: with dignity, love and respect--as true Brothers--but also not without humour, with even a hint of malicious satire. It was always said that the figure of Sarastro was based on the great scientist, Ignaz von Born, Master of Haydn's Lodge Zur wahren Eintracht. But Born had his human failings, too--he was vain and hardly tolerated other views than his own (which were, admittedly, wise and far-reaching). When he took over the new Lodge, which was founded on 12 March 1781, he intended to make of it a kind of society of the sciences, and within a few years he turned it into the elite Lodge of Vienna, filling it with writers, scientists, Catholic and Protestant clerics, government officials -- and Joseph Haydn, who joined in February 1785. This was about six months before Joseph II issued his famous and devastating decree on the Masons (11 December 1785), wherein he sought to centralize them and limit their powers. It was, in fact, as noted earlier, the beginning of the end of the great period of Masonry in Austria (and the beginning of the downfall of Born's Lodge and ultimately of Born as a leading Master-Mason; he resigned from the Craft in 1786, his Lodge having been disbanded on Christmas eve 1785). Born lived until July 1791, just when Mozart entered his new opera in his thematic catalogue (except for the Overture and the March of the Priests, which were only completed before the first performance in September).

Whether, as the romantic legend has it, Born was consulted about the details of the opera, and whether he even knew that Sarastro was to symbolize himself as the essence of tolerance, wisdom and justice, no one will ever be able to tell. But there are some details of Sarastro's character that are not wholly sympathetic and certainly not Masonic: he owns slaves; he describes his slave, the blackamoor Monostatos, as having a soul as black as his skin (racial discrimination, we would say nowadays); he condemns him to be beaten seventy-seven times on the soles of his feet. And to appoint Monostatos as Pamina's guardian, almost enabling him to rape her as she sleeps, is not exactly the act of a wise Master.

Mozart and Schikandeder did not overplay their hand. The basic tenets of Freemasonry are presented with great sympathy, and Mozart was clearly at his best in the scenes which glorify the Englightenment . . . But Sarastro, like Born, is not a perfect man and there is no attempt to conceal the anti-feminist side of the Masons (an aspect which Leopold II, incidentally, also considered ridiculous). . . . the audience in September 1791 went home with the feeling that the Masons were the embodiment of the Josephinian Enlightenment -- and besides, much of the opera was genuine good fun. There was something in it for everybody; connoisseur and shopkeeper left deeply satisfied. The Masons might have hoped that the Craft had been, perhaps, even saved from downfall. But this was not to be; by 1794 Masonry in Austria ceased to exist.

The great Mozart scholar, Otto Erich Deutsch, wrote in 1937 about The Magic Flute's libretto, warning us not to judge it exclusively as a Masonic opera.

More mysterious than the actual connections with Freemasonry is the real history of the work's origin, which has a clearly felt hiatus [between the carefree first section and the solemn second Act] , probably the result of external circumstances, such as the rivalry of the Leopoldstadt Theatre; but despite everything, the libretto is also a masterpiece, having its desired effect on young and old, on rich and poor, then as now and surely for all ages. Even the ungainliness of some of Schikaneder's verses has not stopped some of them from becoming part of the language" (pages 135 - 137).

In his book Mozart. A Life., which was published in 1995, Maynard Solomon presents his readers with interesting comparisons and opinions on Mozart's late Italian operas and the Magic Flute:

" . . . Now, to envisage the probability that he operates on a higher moral plane than we do is for us to lose our moorings, even to glimpse the abyss.

We lose our moorings in Die Zauberflöte as well, where in a riot of carnivalesque metamorphoses, we are asked to validate the most improbable narrative detours and U-turns. Sarastro, a demonic kidnapper, is transformed into a fountainhead of benevolence; the Queen of the Night, a mother passionately seeking to recover her daughter, turns into the embodiment of malevolence; Papageno and Tamino become disciples of Sarastro, though both were initially in the service of the Queen of the Night; Monostatos too changes his allegiance, but in the other direction; Pamina, despite having been abducted by Sarastro and almost raped while in his charge, confesses her own criminality and to all appearances freely converts to the interests of her jailers. Die Zauberflöte is a rescue opera in which the hero arrives on the scene himself crying for help, trembling in fear, and fainting dead away. "Help! Help! Or else I am lost! . . . Ah, save me!"--this is a strange text for a chivalric hero. He has a bow but no arrows, yet despite his defenselessness he is chosen as the perfect knight, now armed with only a magic flute, to rescue Pamina. It is not Prince Tamino but the timorous bird catcher Papageno who twice saves Pamina from rape; and it is Papgeno not Tamino who sings the great love duet with her, "Bei Männern, welche Liebe fühlen." An old crone says her age is eighteen years and two minutes; she turns out to be Papagena. The unpreparedness of these reversals, improbabilities, unmaskings, and remaskings is what is so startling, like turning over a card, switching a lamp on and off, changing light into darkness and back again. Appropriately, the overarching design of the opera embodies the transition from star-flaming night to brilliant sun" (Solomon: 506-507).

"On the evidence of the Da Ponte operas and Die Zauberflöte, Mozart is one of those rare creative beings who comes to disturb the sleep of the world. He was put on earth, it seems, not merely to provide an anodyne to sorrow and an antidote to loss, but to trouble our rest, to remind us that all is not well, that neither the center nor the perimeter can hold, that things are not what they seem to be, that masquerade and reality may well be interchangeable, that love is frail, life is transient, faith unstable. The archaic myths and traditional stories had provided both certainty and assurance that we knew what these old stories were and how they would turn out. And they did not disappoint us. But Mozart's universe is itself uncertain, a maze of doorways to the unknown and the unexpected. Everywhere there are dislocations, fissures, tears, and weak spots; cynicism and disillusionment now permeate his resolutions, corrupt his happy endings" (Solomon: 509).

" . . . though stock characters also populate the Da Ponte operas and Die Zauberflöte and create the illusion that they are performing according to expectations, we often encounter in them a disjunction between type and music; a revelation of unexpected ambiguities and apparently misplaced feelings. Sarastro is purged of his criminality (though not his misogyny) as he revels the splendors of the Temples of Wisdom, Reason, and Nature . . . " (Solomon: 511).

"If the Queen of the Night is evil, we may find ourselves condoning the theft of her child. These metamorphoses are far different from the routine narrative transformations (of Pasha Selim, Titus, Idomeneo, Almaviva) that testify to the workings of mercy, forgiveness, penitence, and reconciliation--not to mention the presumed ultimate beneficence of all misguided rulers--at the close of every exemplary drama" (Solomon: 511).

"Although Don Giovanni commits an incidental murder and Sarastro a kidnapping, the cardinal crimes in the Da Ponte operas and Die Zauberflöte are those aimed against virtue, in the first place seduction and rape. Indeed, the treat of sexual violation is central to all of Mozart's opera buffa and singspiels from Zaide to Die Zauberflöte, although it had been absent in his earlier works in these genres" (Solomon: 512).

"In Mozart's hands, the endangered heroine is more than simply as usefully titillating dramatic trope fed by the confluent streams of classical mythology, the Richardsonian novel, gothic fiction, pornographic literature, Franco-Italian comedy, and Sturm und Drang antityrannical drama. Rather, this trope is an important means of focusing the deep eroticism that characterizes Mozart's late operas. . . . In Die Zauberflöte the only reasonable alternative to live is "death and despair": Pamina will kill herself if she loses Tamino's love; Papageno will hang himself if he cannot find love; Tamino goes through fearsome ordeals to achieve love.

Pamina, subjected to a variety of horrors, of which kidnapping, captivity, coercion, and attempts at rape are only a beginning, is the paradigm of Mozart's endangered heroines. When we encounter the Hamletlike cruelty of Tamino toward Pamina/Ophelia during the ritual silence, and she asks, "And shalt thou den my bridegroom?" as she looks at her dagger, we know, suddenly, that this is no idle fairy-tale entertainment. Tamino's (and Papageno's) silence is not the only reason why Pamina comes to the edge of suicide. equally annihilating are her mother's insistence that she commit murder, her mother's curse ("Thou shalt nevermore be my daughter; be thou outcast forever, be thou forsaken forever"), and, finally, the knowledge that she has been offered by the Queen of the Night to Monostatos as the price of his treachery" (Solomon: 513).

"But Mozart, despite his determination to get even when he himself has been mistreated, understands--at least, in his rational/Masonic creed--that vengeance, because it indulged individual passion at the expense of objective reason, is an insufficient remedy for injustice. . . . Die Zauberflöte offers an ideologically more appropriate response to cruelty and injustice: the rejection of violence, the acceptance of responsibility; the faith in love as a shield against evil. Although it was Sarasto's violent actions--his assertion of the droit de seigneur--that launched the perils of Pamina, she refuses the knife, acknowledges her own sins, and asks for forgiveness. . . . Despite his abjection, however, she will not compromise her love and sacrifice herself to Sarastro. The operas are not only about menace, but also about rescue . . . The French revolutionary "rescue opera," which led to Fidelio already had ample precedent in the operas of Mozart. Brigid Brophy showed that Die Zauberflöte combines two myths: the abduction of Demeter's daughter Persephone by Hades and the rescue of Eurydice from the underworld by the musician-hero Orpheus. Nagel too wrote, "The rescue of a captive woman from the underworld by a loving man is the oldest plot inopera"; he observed further that with Goethe's Iphigenia, Mozart's Pamina, and Beethoven's Leonore "a different, clandestine plot-line asserts itself: how the woman in need of rescue becomes the rescuer." . . . in Die Zauberflöte, it is Pamina in the end who leads Tamino through the caverns of fire and darkness.

These operas try to make things right by bringing to bear every conceivable strategy of evasion and confrontation, opposing power with beauty, innocence, cunning, protest, evasion, irony, and carnivalesque inversion, and finally, by adapting the central formula of opera seria reconciliation, which is the transformation of a miscreant into a simultaneously repentant and forgiving ruler. The benevolent sun-priest dedicated to monogamous marriage, wisdom, and reason is no longer the lustful Sarastro who kidnapped and coerced Pamina and left her defenseless against his servant's assaults: he has been at once transfigured and neutralized. The proper antidote to the misogyny of Don Alfonso and Sarastro is a joyous wedding. In all of the operas, the closes approximation to a satisfactory resolution resides in the marriage sacrament, where a consecrated private space replaces the social sphere as the locus of utopia, representing a leap of faith, the pledging of life, the promise of continuity, and even the microcosmic equivalent of the godhead:

Man and Wife, and Wife and Man

Reach even to divinity.

Mann und Weib, und Weib und Mann

Reichen an die Gottheit an.Mozart's operas are dramas of desired transformations" (Solomon: 514-515).

In 1999, Robert W. Gutman writes in his Mozart book:

"The Magic Flute's comic and farcical elements and its fantastic turns of plot--inspired by the Wieden theater's remarkable stage machinery--rotated about a solemn dramatic core: an allegory of a young prince's entry into a noble brotherhood. Mozart wished this compound of popular theater and a symbolic representation of Freemasonry's spiritual attributes to remind the Viennese of its contribution to the city's ethical life. Schikaneder had become a member of the Order during his days in Regensburg, a center of its Rosicrucian branch, and the scenario he and Mozart concocted evokes its symbols, in particular numerology: the action, text, music and stage directions of more than one scene interlock with the elaborate protocols of the Lodge's system of degrees, the verses at times paraphrasing the very rubrics of the secret ritual. As to what Sarastro and his temple stood for, few in the Wieden theater could have been in doubt." (Gutman: 724).

Since we have opened our comments here with Eckermann's report on Goethe's opinion of this opera, it might, perhaps, be interesting to feature Harry Haller's Goethe dream, in Hermann Hesse's nove., Der Steppenwolf:

"'Sie haben, Herr von Goethe, gleich allen großen Geistern die Fragwürdigkeit, die Hoffnungslosigkeit des Menschenlebens deutlich erkannt und gefühlt . . . Dies alles haben Sie gekannt, sich je und je auch dazu bekannt, und dennoch haben Sie mit Ihrem ganzen Leben das Gegenteil gepredigt, haben Glauben und Optimismus geäußert, haben sich und andern eine Dauer und einen Sinn unsrer geistigen Anstrengungen vorgespielt. Sie haben die Bekenner der Tiefe, die Stimmen der verzweifelten Wahrheit abgelehnt und unterdrückt, in sich selbst ebenso wie in Kleist und Beethoven . . . Das ist die Unaufrichtigkeit, die wir Ihnen vowerfen.'

Nachdenklich blickte der alte Geheimrat mir in die Augen, sein Mund lächelte noch immer.

Dann fragte er zu meiner Verwunderung: 'Die Zauberflöte von Mozart muß Ihnen dann wohl recht sehr zuwider sein?'

Und noch ehe ich protestieren konnte, fuhr er fort: 'Die Zauberflöte stellt das Leben als einen köstlichen Gesang dar, sie preist unsere Gefühle, die doch vergänglich sind, wie etwas Ewiges und Göttliches, sie stimmt weder dem Herrn von Kleist noch dem Herrn Beethoven zu, sondern predigt Optimismus und Glauben.'

'Ich weiß, ich weiß,' rief ich wissend. 'Weiß Gott, wie Sie gerade auf die Zauberflöte verfallen sind, die mir das Liebste auf der Welt ist! Aber Mozart ist nicht zweiundachtzig Jahre alt geworden und hat nicht in seinem persönlichen Leben diese Ansprüche an Dauer, an Ordnung, an steife Würde gestellt wie Sie! Er hat sich nicht so wichtig gemacht! Er hat seine göttlichen Melodien gesungen und ist arm gewesen und ist früh gestorben, arm, verkannt---'

Der Atem ging mir aus. Tausend Dinge hätten jetzt in zehn Worten gesagt werden müssen, ich begann an der Stirn zu schwitzen.

Goethe sagte aber sehr freundlich: 'Daß ich zweiundachtzig Jahre alt geworden bin, mag immerhin unverzeihlich sein. . . . " (Hesse, Steppenwolf: 106 - 107; Please note: Since literature by Hermann Hesse can not be translated, yet, without violating copyrights and since, on the other hand, literature should best not be summarized, we would ask for your patience until we locate an English edition of this work to quote this passage from. Perhaps this German quote can even encourage you to undertake some research on your own?).

Sources:

Eckermann, Johann Peter. Gespräche mit Goethe in den letzten Jahren seines Lebens. Berlin und Weimar: 1982. Aufbau-Verlag (ehemalige DDR).

Einstein, Alfred. Mozart His Character, His Work. First Edition, Sixth Printing. London. New York. Toronto: 1961. Oxford University Press.

Gutman, Robert W. Mozart. A Cultural Biography. New York, San Diego, London: 1999, Harcourt Brace & Company.

Hesse, Hermann, Der Steppenwolf. Bibliothek Suhrkamp, Band 226. Frankfurt am Main: 1973. Suhrkamp Verlag.

Hildesheimer, Wolfgang. Mozart. Translated from the German by Marion Faber. New York: 1977, Farrar, Straus and Giroux. The Noonday Press.

Köchel, Dr. Ludwig Ritter von. Chronologisch-thematisches Verzeichnis sämtlicher Tonwerke Wolfang Amade Mozarts. Dritte Auflage bearbeitet von Alfred Einstein. Ann Arbor, Michigan: 1947, Verlag von J.W. Edwards.

Kolb, Annette. Mozart Sein Leben.Erlenbach-Zürich: 1958, Eugen Rentsch Verlag.

Robbins Landon, H.C. Mozart The Golden Years. Thames & Hudson: 1969.

Robbins Landon, H.C. 1791 Mozart's Last Year. New York: 1988, Schirmer Books, A Division of Macmillan, Inc.

Solomon, Maynard. Mozart A Life. New York: 1995, Harper Collins.

To the Page:

The Magic Flute

and Beethoven